This page explores the world of John Agnew, resident in Bloomfield House from 1831, often Sovereign of Belfast, urbane, tall and handsome - a perfect gentleman who enjoyed horticultural pursuits.

He benefited from a £500 annual income from the town's markets, but as the town's chief magistrate he was caught up with sectarian riots, having to report to a Select Committee of the House of Commons.

Through marriage he enjoyed good connections to many important families - but who was he? Where did he come from?

The next occupant of Bloomfield House, from late in 1831, was John Agnew, “an intimate of Lord Donegall’s family and often Sovereign of the Town”. The two attributes go together “hand in glove”, symptomatic of the undemocratic nature of Belfast’s governance in these years.

‘You may know a man by the company he keeps’, according to the famous proverb. In John Agnew’s case that's well-proven by this quote from Saunders’s News-Letter, Tuesday 16 November 1819, page 2:

The Chace [Chase].— On Wednesday last the Marquis of Donegall’s harriers had one of the fleetest and longest runs ever known in this county. They found at the blacksmith’s shop, and first took their direction for Doagh — then doubled, and made for Carrickfergus, across the common, four miles beyond which place they killed; — having run over the distance of about twenty-five miles in two hours and twenty-five minutes. Among the foremost in the chace [chase], we particularly remarked the Lord E. Chichester, Wm. Wallace, Esq. John Agnew, Esq. and the huntsman. — Belfast News-Letter.

And what of the Ballyhackamore townland in which John Agnew's new home, Bloomfield House, was situated?

Lieutenant G.F.W. Bordes, wrote the Statistical Report on the Parish of Holywood, Co. Down, in September 1834 for the Ordnance Survey Memoirs (source: O.S. Memoirs, Co.Down II, Vol.7, Institute of irish Studies, QUB, 1991)

Under Mills, Bordes noted that 'There is a large flour mill at the south western point of the parish called Beer's mills, with a mill pond.'

Under the heading of Townlands, Proprietors and Agents, he noted, 'Ballyhackamore: Reverend J. Cleland of Dundonald, agent his son.'

For the heading Social and Productive Economy, there is a very precise Census of Population:

Ballyhackamore, 126 houses, 120 families, 47 employed in

agriculture, 33 in trades, 40 in other occupations, 611 total

inhabitants, 275 males, 336 females, 115 males above 20; 2 farmers

employing labour, 7 labouring farmers, 40 labourers employed by farmers,

1 flour mill, 11 capitalists, 10 non-agricultural labourers, 8 male

servants above 20, 2 male servants under 20, 27 female servants, 36

employed in handicraft.

John Agnew himself mainly features in the press from the early 1820s when initially he would have been appointed one of Belfast’s 12 burgesses before first being appointed Sovereign in 1823. As Sovereign, he loomed large across the 1830s when cholera and other fevers were endemic. His earlier years, however, and his family origins, remain quite elusive.

New Grove on the way to Bloomfield

Belfast News Letter, 4 September 1829

DONEGALL-SQUARE.

TO BE LET, FROM 1ST NOVEMBER NEXT,

THE HOUSE at present in the possession of Major D’ARCY; also, that lately occupied by JOHN AGNEW, Esq. Those Houses will be found fitted up in the best manner, to afford accommodation and every convenience for large and respectable families; each House having excellent STABLING, COACH and COW HOUSES, SADDLE-ROOMS, YARDS, &c. &c.

Apply at the Timber-Yard of

ADAM McCLEAN & SON.

Belfast, 2d September, 1829.

In the 1824 Pigot's Directory, Major Thomas D'Arcy's address is 8 Donegall Square South. Like John Agnew, Arthur Crawford and John Holmes, he is listed under Nobility, Gentry and Clergy. So, although we don't yet know when John Agnew moved in to the Donegall Square house, we know that he left there in 1829.

Given the references to Arthur Crawford on the previous webpage, it seems likely that Agnew moved into Bloomfield House in autumn 1831.

So where did he and his family live during those couple of in-between years?

A newspaper story provides the answer.

The version transcribed below is from Dublin's Freeman's Journal of 1 December 1830, quoting from the Northern Whig. The Belfast News Letter also carried the same story on 30 November 1830.

On Friday night, between ten and eleven o’clock, as John Agnew, Esq., was returning to his residence at New Grove, [when] by Newtownbreda, he discovered the body of a man lying on the road, a short distance of the church.

Mr. Agnew procured the assistance of the police, who had the body immediately removed to Mr. Clawson’s, of Newtownbreda, where the assistance of Dr. McClure was instantly afforded, but life was quite extinct. On examination of the papers found on the deceased, he proved to be a Mr. Wyne, a linen merchant belonging to Armagh, and, from the valuable documents found on him, it is quite evident that he did not come by his death through any violent means, prompted by a desire of plunder.

On his person were found a silver watch, £40 in money, and a banker’s check from a most respectable house in Belfast for £131. From the evidence produced on the coroner’s inquest held next day (and which recorded the verdict of accidental death), it appeared that Mr. Wyne had attended the Belfast market on Friday, but no clue was afforded by which to elucidate the cause of his unfortunate death. It is premised he must have fallen from a very high footpath, and that his death was occasioned by his head coming into contact with the highway.

On Sunday, his friends from Armagh had the body removed in a hearse, accompanied by every mark of respect and affection. — Northern Whig.

New Grove, between Edenderry and Drumbo, is a fine Georgian house, single-storey and assymetrical at the front, two-storey at the back.

It was mentioned (see on the right) by George Tyner in his The Traveller's Guide Through Ireland: Being an Accurate and Complete Companion to Captain Alexander Taylor’s Map of Ireland, Dublin, 1794.

New Grove (or sometimes Newgrove) was in the family of Roger M.H. McNeill, certainly from 1759 and beyond 1815.

Leaving Lisburn you meet another turnpike, and on the L. Belsize, the seat of Mr. Hudson.

About 1½ mile from Lisburn close to the road, and between it and the river is Lambeg church, and further to the R. beyond the Purdistown road, is Hillhall castle ruins; and half a mile further on the L. is Derryaughy church.

2½ miles from Lisburn on the R. close to the road, is Drumbeg church, and further to the R. is Drumbo church; a quarter of a mile further on the L. is Willmount, Mr. Stewart’s, on the R. a charter-school, and further to the R. Thornhill, Mr. Maxwell’s.

3½ miles from Lisburn on the R. is Newgrove, Mr. McNeill’s; and a little further Edenderry, Mr. Beer’s.

Roger McNeill offered a reward through the Belfast News Letter for the conviction of the person who'd stolen timber from New Grove in January 1759. The McNeills (there's a Roger sen. and a Roger jun.) are interesting characters and it looks as if Roger jun. was declared insolvent by 1815 (see the McNeill dealings and some correspondence held by PRONI).

On 24 December 1809, Daniel McNeill, the eldest son of Roger McNeill jun., married Jane, the eldest daughter of Thomas Bunbury Isaac of Holywood House and formerly of Bloomfield House (the marriage was listed in the Belfast Monthly Magazine, December, 1809).

McNeill, sometimes listed as 'of Ballylesson' and 'of Knockbracken', leased his New Grove house to different tenants. These included John Younghusband (1752-1843) who lived at New Grove in 1793, but by 1805/6 was living in Ballydrain (nowadays Malone Golf Club) which had belonged to the Stewarts (his relatives through marriage).

John Agnew and his young family lived in New Grove, probably from August 1829 through to 1831.

The Belfast News Letter, for Friday, 22 January 1830, carried the announcement of a birth:

At Newgrove, on Friday last, [15 January 1830], the Lady of JOHN AGNEW Esq. of a son.

An advertisement on page 3 of the Belfast News-Letter, Friday 27 September 1833, likely reveals that John Agnew's family was in the process of moving to Bloomfield House:

'To be let from the first November next, THE HOUSE, OFFICES, and GARDEN of NEWGROVE, with any quantity of the Demesne that may be required. ... Apply to Mr. [N.] Batt, Esq., Purdysburn ...'

New-Grove [sic] was again advertised two years later , 'having undergone a thorough repair'. (Northern Whig, Monday 6 April 1835, page 3).

In 1837, Samuel Lewis, in his Topograhical Dictionary,

lists William Russell at Edenderry House and John Russell at New Grove. Both these brothers were married to daughters of the

banker John Holmes (for ease of reference labelled here as "John Holmes II").

What a small and interconnected community! John Agnew was married to a granddaughter of that same banker John Holmes II (she was a daughter of John Holmes II's son, John Holmes III).

RH pics: Please click to enlarge. The two photos of New Grove are used with kind permission and remain © Stuart Blakley. The Ordnance Survey Memoir for Drumbo Parish (c.1833) mentions that "New Grove, the residence of Councillor Thomas Hutchenson, [is] a small but desirable residence." In his book Buildings of North County Down (UAHS, 2002), Charles Brett suggests that "Roger McNeill seems to have been a Volunteer Officer in 1780" - borne out by this from the Belfast News Letter, November 1780 (as quoted here in Ecclesia De Drum (Chapter 7) by Matthew Neill):

The proceedings began at about twelve noon, when the arrival of the Reviewing General, Roger McNeill Esq., was announced by the firing of a cannon. Seven companies made up the two battalions taking part. The Blues battalion comprised: Lambeg Volunteers (Capt. Bell), Lisburn Blues (Capt. Burden), Dunmurry Volunteers (Capt. Johnson). Opposing them was the Red battalion made up of: Drumbridge Volunteers, Lieut. Michel (Capt. Stewart acting as director of the mock engagement), Purdysburn Volunteers (Capt. Wilson), Ballylesson Royals (Capt. McNeill [Roger jun.]), and Lisburn Fusiliers (Capt. Jones). The objective of the Blues battalion was to force a passage over the river at three points, first at the weir downstream from the bridge, second at the Drum bridge and third by pontoon on the tongue of land between the river and the canal. Under their commanding officer, Capt. Johnson. the troops ably performed the whole of the day's service, without indulging themselves in any refreshment. The land around Miss Maxwell's Drum House was most suitable, the weather favourable, the spectators were delighted, and the troops returned to their quarters in a regular and peaceable manner.

Sorting out the money men

So who was John Agnew and where did he come from?

The name "John Agnew" appears frequently in the many leases of the financially troubled Second Marquis of Donegall, an inveterate gambler.

Agnew features in the batches from 1799 to 1802, as a host of creditors sought payments from the new Marquis who had inherited one of the greatest landed estates in Ireland. These leases usually have John Agnew as

a second or third ‘part’ along with James Dashwood and William

Macgeorge. They are variously described as being “all of London”, or “of

New Bond-street” or “of Middlesex”.

The name John Agnew appears again in the leases dated between 1822 and 1832. This was the period when the Marquis was raising money by granting "perpetual leases" which necessitated the payment of an additional lump sum.

Most of these 1822-1832 leases pair John McCance (1772-1835) and John Agnew as one of the ‘parts’. The two were related by marriage (see the Holmes family PDF below) - more interconnections!

LH pic: John McCance of Suffolk, Dunmurry, an important figure in the development of the linen trade. He played a significant role in the life of Belfast, both as a politician and a businessman. He became Chairman of the Northern Banking Company and was elected MP for Belfast in January 1835, but died in London in August that year.

In fact, the John Agnew mentioned in relation to the Donegall leases is not one person, but two quite different people. The second is the one relevant to Bloomfield House - and he is not a son of the first (unless kept as a secret!).

For the sake of clarification, the first was John Agnew (1759-1812), of Whitton Park, Middlesex. He had both a Scottish address (Drumbovie, Wigtownshire) and an English one and he made his fortune with the East India Company.

After his return to England in 1795 he invested his money in a bank partnership with Walwyn, Strange, Dashwood, Steward and Macgeorge of 150 New Bond Street. He became the MP for Stockbridge in 1799 but failed to be re-elected in 1802. His public career ended when the bank failed a few years later. Lord Minto claimed that the failure was due 'to the misconduct of one of the partners, Mr Agnew.'

This John Agnew married Elizabeth Stevens in 1790 in Bombay. Some genealogical websites state that they had two children: Henry Crichton Agnew (1797-1854) and Elizabeth Amelia Agnew (c.1795-1868). However Thorne's History of Parliament (see here) suggests that there were 2 daughters and one son, the latter predeceasing his father.

John Agnew of Bloomfield, the second of the two John Agnews, has proved much more difficult to track down.

His name has, to date, failed to surface in church records (apart from his marriage in St Anne's Church in Belfast), nor does a portrait exist.

The surname is a common one, though an educated guess might allow that a comparatively wealthy and local Agnew of the period could be related to the Agnews of Kilwaughter Castle, Co. Antrim. For excellent coverage of that family and its John Nash home, see here.

More of that later. First, the background and the available and reliable information.

John Agnew and the Holmes family

Important details emerge from a grave headstone inscription in Comber Graveyard, Co. Down, recorded by R.S.J. Clarke in Gravestone Inscriptions Vol.5: Co. Down, 2nd edition, Ulster Historical Foundation, 1984. His transcription is given below the following photo gallery - please click on the pics to see the full photos.

HOLMES

This vault belongs to

the family of the late John Holmes, Esq., [= John Holmes II] of the County Down and

Belfast, many members of which were interred here. Also John Agnew

Esq. who died at Donaghadee 4th August 1844 aged 54. He married Anne

Lindsay Holmes, grand-daughter of John Holmes [II]. John Agnew, Esq., his

only son who died in Nov. 18[5]8 [actually 1855] aged [? …] and Anne Lindsay

Agnew, his only daughter, who died on the 13th [actually 15th] [May] 18[81]

aged [?…]. Isabella Holmes, youngest daughter of John Holmes [III], born 10th

May 180[5], died 17th May 18[99]. This is [finally] closed.

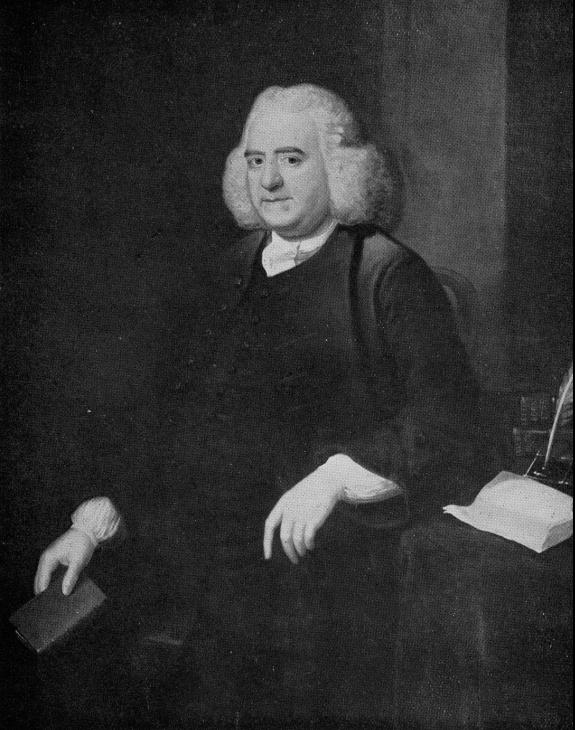

RH pic: John Holmes, the elder (1703-1779) - John Agnew's great grandfather-in-law and referred to on this website as "John Holmes I".

It's from a portrait by R. Hunter which belonged to the Blakiston-Houston family of Orangefield.

There follows here a considerable digression about the Holmes family into which John Agnew eventually married.

However, the family was an important one in the history of Belfast and it's worth exploring.

John Holmes I, pictured above, was one of a prominent Belfast merchant family. He had three brothers: Robert, a goldsmith in Dublin; Hugh, a merchant in Antigua, West Indies; and James, about whom very little is known.

The John Holmes referred to on the Comber gravestone (above) is not this John Holmes (1703-1779), but his son, John Holmes II, (sometimes understandably referred to as John Holmes, jun. (c.1745-1825)). We'll call him John Holmes II.

Further confusion is caused by there being another John Holmes jun. (c.1779-1825), son of John Holmes II.

This will be John Holmes III, very frequently referred to as John Holmes jun. in contemporary accounts.

John Holmes I (1703-1779) had three children: John (John Holmes II, "the late John Holmes Esq." of the Comber gravestone), Mary and James.

- Mary Holmes married Thomas Houston, a woollen draper from Dublin. Their son, John Holmes Houston, eventually lived in Orangefield House and was a prominent Belfast banker.

Faulkner's Dublin Journal, Saturday, 23 Nov - Tuesday 26 November, 1765:

Marriages.

Saturday last, at Belfast, Mr.Thomas Houston, an eminent Woollen Draper of the city of Dublin to the amiable Miss Holmes, only Daughter of Mr. John Holmes, an eminent Merchant of that Town, with a Fortune of £5,000.

- James

Holmes was an important merchant along with his brother John. They had

trading links with Philadelphia and the West Indies. James was appointed

the first US Consul in Belfast in 1796. He married into the Davis

family of Newry and they traded as Holmes and Davis, importing and

exporting with the West Indies, Russia and Italy.

- John Holmes II (pictured farther below) was a particularly significant figure in the history of Belfast.

A leading merchant and banker, the advertisements on the right, from page 1 of The Belfast Mercury; or, Freeman’s Chronicle for Friday, 10 September 1784, reveal some of his dealings in the shipping trade, along with some of his key colleagues in the merechant life of Belfast.

He was certainly an important banker - one of those who made up the "Bank of the Four Johns" (Ewing, Holmes, Hamilton and Brown). Established in 1787, it was Belfast's second bank, properly known as the Belfast Bank (the first bank in Belfast, run by Mussenden, Adair and Bateson, opened in 1752 and closed five years later).

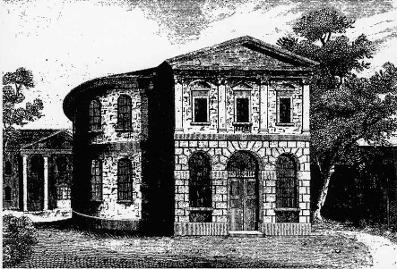

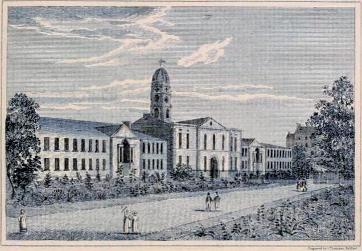

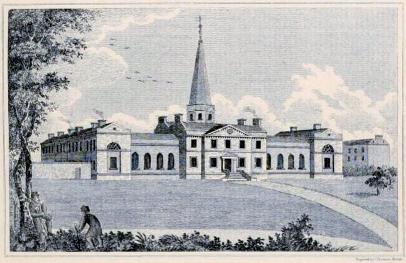

The First Presbyterian Church in Rosemary Street, 1783. The Second Presbyterian Church, 1790 (demolished in 1964), is directly behind it.

Like all of his banking colleagues, John Holmes II was a member of Belfast's First Presbyterian Church in Rosemary Street. He was mentioned as a stipend payer in a 1775 church listing. He was also a subscriber to the church's "Building Fund for the Present Meeting House", April, 1781.

In 1785, John and his brother James, with £25 each, headed the list of Subscribers and Patrons of the new Belfast Academy in Academy Street

(the school eventually became the Belfast Royal Academy in Cliftonville Road). The

list included Bloomfield's neighbours: William Rainey, Rainey Maxwell

and John Goddard, all of Greenville, and Thomas Bateson, jun., of

Orangefield.

John Holmes II became the Belfast Academy's

first President in 1786; he was still there in 1822 when, as President

and Trustee, he contributed a further £20 to a new subscription.

The Academy's

founding principal was Rev. Dr. James Crombie, minister of the First Presbyterian Church.

On 12 April 1792, nine of the Academy's pupils rebelled against the lack of an Easter holiday.

Armed with pistols, they 'holed up' in the mathematics room. Shots were fired.

Despite the pleas of John Holmes II, who narrowly missed being hit by a bullet; despite water ineffectually being poured down a chimney; and despite the attempted intervention of the Belfast Sovereign, the Rev. William Bristow, the pupils would only agree to surrender on the promise of no punishment.

An 18th century flintlock pistol. Pic by Older Firearms and licensed for use here through a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Licence.

They were given that promise and then surrendered. The next day they were whipped and expelled.

John Holmes II married Isabella Patterson from Comber

(perhaps a daughter or grand-daughter of James Patterson (died 1761) who had owned a malt

kiln and distillery in what is now Killinchy Street, Comber).

LH pic: John Holmes II (c.1745-1825), the Belfast merchant and banker.

From a portrait which belonged to the Blakiston-Houston family of Orangefield.

This was the grandfather of John Agnew's wife.

John and Isabella's many children and grandchildren married into the Joy, McCance and Russell families - all influential Belfast families. Some relatives had important connections to the United Irishmen, and certainly John Holmes II himself was an active supporter in the early 1790s.

The PDF on the right details many of the known Holmes family marriages; also some of the Holmes' links with the West Indies and the USA; Wolfe Tone's mention in 1796 of a packet sent to Philadelphia via

Hugh Holmes and Robert Rainey; Holmes and Rainey's involvement with the Friendly Sons of St Patrick; and the wills of Hugh Holmes of Antigua.

There's no doubt that John Holmes II, often

with his brother James, played an important role in Belfast's highly

turbulent times in the latter years of the 18th century. The PDF (below right) features most of the relevant passages about Holmes culled from Henry Joy's Historical Collections relative to the Town of Belfast ..., Belfast, 1817.

They begin with one relating to his father, John Holmes I, but the rest cover the concerns of John Holmes II about trade; parliamentary reform; struggles between the British and Irish parliaments; building the White Linen Hall; Roman Catholic emancipation; the United Irishmen; and the Supplementary Corps of the Yeomanry Infantry.

John Holmes II was also Treasurer and, briefly, Vice-President (1800-1801) of The

Belfast Library and Society for Promoting Knowledge (later known as the

Linen Hall Library).

Coinciding with his retirement from office and the Library moving into the "room over the centre part of the White Linen Hall" in 1802, Holmes gave the Library a copy of a French Encyclopedia.

It would be particularly good if it had been L'Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers by d'Alembert and Diderot - originally in 28 volumes, though a further seven were added between 1776 and 1780. However, the Library's current catalogue boasts two volumes of Brisson's 1781 Dictionnaire raisonné de physique; so forget Rousseau and Voltaire: perhaps Brisson was the gift.

John Holmes II was involved in land dealings all over the town of Belfast - in Shankill, the Falls, Malone and Cromac. He and his banking colleague John Ewing built the Arthur Street Theatre and, in 1792, leased it to Michael Atkins, comedian, at £72 per annum along with a guaranteed supply, in perpetuity, of free tickets! (See PRONI D2646/2/1)

... yielding and rendering unto the said John Holmes and John Ewing their executors, administrators and assigns four passes or tickets containing full and free liberty of admission into the premises hereby demised for the purpose of being present at and seeing all plays, farces and other exhibitions entertainments or performances which may be performed represented or exhibited therein, upon everyday in the year on which said plays, farces or other exhibitions entertainments or performances shall or may be so performed represented or exhibited, said passes or tickets to be transferrable and to contain liberty of admission into any part of the playhouse and to be rendered and given up upon demand, that is to say two of such tickets to the said John Holmes his executors, administrators or assigns and the other two to the said John Ewing his executors, administrators or assigns or in default or refusal thereof YIELDING AND PAYING unto the said John Holmes and John Ewing their executors administrators or assigns the yearly [rent] or sum of one hundred pounds sterling in lieu and place of the [tickets] herein before reserved the said reserved yearly rent of seventy-two pounds or one hundred pounds as the case may happen ...

Above: Old Theatre (1793-1871), Arthur Square, Belfast - a watercolour illustration by Joseph William Carey (1859-1937) and Richard Thomson (dates?), probably based on a much older print. This version was created for the 1824-1924 Centenary Volume published in 1925 by the Northern Banking Co. Limited, Belfast, using the Marcotype Process.

Meanwhile, John Holmes II seems to have had business dealings with Donaghadee’s Packet Boat business.

James Arbuckle, the customs collector at Donaghadee, in a letter to Lord Hillsborough (later the Marquis of Downshire) dated 25 July 1791 (PRONI D607/B/314), writes:

“ ... Holmes, the banker, has been here about the inn. He now sees the

ruinous state of that wretched edifice so clearly that he thinks the

whole ought to come down, and to build de novo a neat, clean, plain

accommodating inn in the place of it. ...”

John Holmes II (and possibly his brother James)

retired to Donaghadee at the end of the 18th century.

Perhaps John Agnew also retired to Donagadee in his last year or two - which would

explain his death there in 1844 (unless he died while travelling between Donaghadee and Portpatrick or vice versa, a two hour boat journey).

So far I've failed to identify the

precise location for John Holmes II's not insubstantial residence in

Donaghadee's Main-street. He also owned a

meadow nearby, along with lands at Glastry, between Ballyhalbert and

Kircubbin.

A 1910 postcard featuring Donaghadee town and harbour.

This next PDF provides many details about John Holmes II's properties in Donaghadee:

One of Martha McTier's letters to William

Drennan in Dublin, written early in 1801, states that "John Holmes goes to Donaghadee

having now no child unmarried but his son ..."

Looking at the details in the Holmes family PDF above (beside the picture of John Holmes II), that one remaining unmarried son in 1801 (and indeed the only surviving son) was John Holmes III.

The Belfast First Presbyterian Church's 1812 list of stipend payers includes John Holmes of Donaghadee. That entry is followed by one for his son, John Holmes, jun., i.e. John Holmes III, though as will become clearer later on, it seems likely that he was more often in Bath, England, much of the time.

John Holmes II is mentioned in the correspondence of David Ker of Portavo. Writing to his brother Richard G. Ker of Red Hall on 6 November 1791, David states "... a high opinion I have of his [John Holmes'] judgement and candour."

On 28 February 1820, to his brother, then in London, he writes: "I was rather unfortunate in finding Mr. Martin out of Town and Mr. John Holmes gone to Donaghadee to remain till Wednesday."

Both John Holmes and John Holmes jun. (II and III) appear as supporters of Allan Richey in an advertisement on page 1 of the Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Saturday 24 January 1807. It lists the names of 13 such people who promise to pay specific sums of money for information about the person who, on 9 December 1806, had ‘put into the Donaghadee Post Office a number of anonymous letters directed to several Merchants and others in Belfast, tending to vilify the Character of ALLAN RICHEY, of Donaghadee, as a man, and to ruin him as a Merchant’.

The three top donors, at £11 7s. 6d each, were John, John jun., and Alexander McMinn, Herdstown.

At some point, John Holmes II and his wife probably returned from Donaghadee to Belfast as old age set in - it's unlikely they ever actually gave up their Belfast home.

The Belfast News Letter for 22 April 1823 has the death of Mrs Holmes, "wife of John Holmes of Belfast".

A.G. Malcolm, in his 1851 History of the Belfast General Hospital, noted the death on 1 September 1825 of "John Holmes, Esq., aged 80, an eminent merchant, and banker for upwards of half a century."

In fact, as we'll see, John Holmes II had outlived his son, John III, by several months.

Pigot's Commercial Directory of Ireland, 1824, in a listing of the Nobility, Gentry and Clergy of Belfast,

includes John Agnew Esq. (no address given); John Holmes Esq., 14

Donegall-place; Mrs [Robert] Holmes, 12 Donegall-place; Arthur Crawford,

Bloomfield.

The information in Pigot's 1824 agrees with that in Bradshaw's Belfast General and Commercial Directory for 1819.

John Holmes at No.14 was designated "banker".

Bradshaw also confirms Mrs Robert Holmes at 12 Donegall Place (perhaps the widow of Robert, son of James, gold and silversmith, who had been apprenticed to Robert Holmes of Dublin). See the Holmes family PDF above.

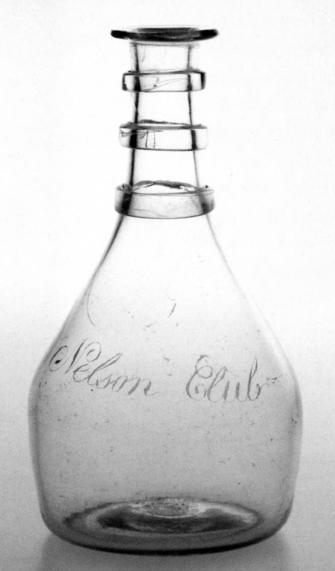

The 1819 Bradshaw's has John Agnew, gent., listed with his residence as "Nelson Club House".

That Club House was also in Donegall Place which had been created in the mid 1780s, initially with the name "Linen Hall Street" before that designation was transferred to the street at the other side of the White Linen Hall (pictured on the right, built in 1784

and home to the Linen Hall Library for 90 years from 1802).

The loyalist Nelson Club, formed in 1805 after the Battle of Trafalgar, occupied an extensive dwelling house in Donegall Place; its premises extended back to Callendar Street. When sold at auction in October 1833, it was stated to be "held under the Marquis of Donegall, for lives renewable for ever, at the yearly rent of £7, 1s. 3d".

Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 29 August 1812:

On Wednesday LAST, a most numerous meeting of the Nelson Club dined together, at their Club House, in celebration of the late glorious victory obtained by our gallant Countryman, Marquis Wellington. Thos. Verner, Esq. was in the Chair, with George Bristow, Esq. as Vice- President. The dinner and wines were of the first description. During which the excellent band of the Dumfries Military played some favourite patriotic airs; and the company, highly delighted with their entertainment, did not separate till a late hour. The following were among the toasts upon this occasion: The King, The Prince Regent, Marquis Wellington, three times three, Memory of Lord Nelson, three times three, … The Glorious Memory, three times three, The Marquis of Donegall, three times three. In the course of the evening the Nelson Club House was brilliantly illuminated, and two barrels of ale were distributed among the assembled populace.

LH Pic : One of a pair of Nelson Club decanters in the Ulster Museum. Kim Mawhinney, writing in the Irish Arts Review, Winter 2005, Page 142, describes them as "quite crudely engraved ... probably made at the Benjamin Edwards Glasshouse which was situated in Belfast at the Long Bridge." Read the article here.

Pic © Trustees of the National Museums and Galleries of Northern Ireland. Photograph by Bryan Rutledge.

Donegall Place was then the fashionable place to live.

This is George Benn writing in 1877 (A History of the Town of Belfast):

... the present Donegall Place, [was] intended for the private houses of the wealthy inhabitants of the town, and which it continued to be for about half-a-century. It is not very many years since that not a single shop, hotel, or place of business of any kind existed in it. The leading gentry had exclusive possession, Lord Donegall's own house being that on the corner, now the Royal Hotel.

Writing in 1896, the Rev. Narcissus G. Batt also remembered Donegall Place as a quiet street of private houses, some with gardens and trees to the rear. "The residents were either merchants of the town, or country gentlemen who came to Belfast for society in winter, as fashionable people now go to London for the season."

The Holmes' neighbours were the likes of Sir Stephen May (his house eventually replaced by Anderson and McAuley's buildings); Mrs May; three, possibly four, households of Batt families; James Douglas of Mount Ida, said (by Michael Ferrar) to have been the fourth richest man in Belfast in 1809, having been bequeathed a large fortune by the merchant Waddell Cunningham; James Crawford, wine merchant (who grew up in Bloomfield as one of Arthur Crawford's sons); Dr John MacDonnell; the Nelson Club; and Thomas Ludford Stewart at the corner of Castle Place (opposite Sir Stephen May's house).

John Holmes III, the father-in-law

John Holmes, jun., designated as John Holmes III to clarify who's who, was most likely born around 1773.

Above pic: Triumph of Love and Folly by William Elmes (c.1760-1815).

George IV with Queen Charlotte who's kept him quiet with a bottle of opium. (Library of Congress - British Cartoon Prints Collection.)

The letter already referred to, from Martha McTier to William

Drennan in Dublin, written early in 1801, about John Holmes II going "to Donaghadee

having now no child unmarried but his son," continued with the revelation that John Holmes III "would gladly get Miss Warre".

"The father [James Warre of London] offers to give his house, £500 a year at present, and l5 [£5,000] at his death, but 'tis thought it will not do."

Drennan thought Miss Amelia Warre was "a fine, agreeable girl", and in November 1800, Martha described her to Drennan as a "tall, blooming girl of sixteen", though a month later she expanded that to "a fine, healthy, fat, and fair natural girl of sixteen".

RH text box: The wording on a

memorial stone at Coldwell Rocks.

In The Banks of Wye; A Poem. In Four Books

(London: Vernor, Hood & Sharpe, 1811), Robert Bloomfield (1766-1823) mentions the

tragic drowning of Amelia's brother. See here (lines 263-288).

Sacred

to the memory of JOHN WHITEHEAD WARRE, who perished near this spot,

whilst bathing in the river Wye, in sight of his afflicted parents,

brother, and sisters, on the 14th of September, 1804, in the sixteenth

year of his age.

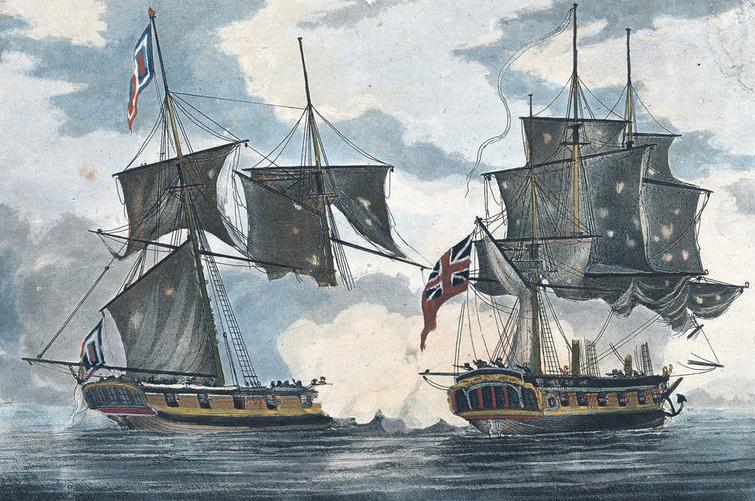

Amelia's mother, Elinor Warre, was a sister of Cunningham Greg one of Belfast’s leading merchants.

Thomas Greg, the father of Elinor and Cunningham, had profited considerably

during the Seven Years’ War (1759-1763) between Britain and France,

thanks to his business partnership with Waddell Cunningham, a Co. Antrim

man then living in New York.

Their merchant ships traded in flax seed,

tobacco, sugar and

cotton, and it seems they also played both sides - as privateers for the

British, plundering French ships, but simultaneously involved in

illegal trading with the French enemy, a common enough practice at the time.

After the war, Cunningham and Greg established a sugar

plantation, named “Belfast”, on the island of Dominica in the West

Indies. Cunningham returned to Belfast, not least to avoid court cases in New York. Both men played highly important

roles in the development of Belfast and its harbour - including a glassworks and a pottery.

Above pic: The 'Antilope Packet' beating off 'Le Atalante', a French privateer, in the West Indies - a watercolour by William Elmes (c.1760-1815). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

So

James Warre, an important wine merchant whose family

owned the leading Warre's Port company, was clearly unable to provide a

sufficiently large dowry to satisfy the Holmes family. Nonetheless, his wife's

family connection to the "Belfast" sugar plantation in Dominica may

indeed be relevant in some way to John Holmes III’s eventual marriage.

Presumably the Attorney-general of Dominica was more wealthy than Mr Warre!

This is from Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, April 1802, page 256:

John Holmes jr.,

Belfast, and Miss Daniels [sic], only daughter of T.,[sic] Attorney-gen.

Island Domingo [Dominica], at Thetsham, Norfolk.

The Belfast News Letter, 13 April

1802, also listed the marriage.

"Thetsham" might be a misheard word, for

the marriage took place on 1 April 1802 in St Mary's Parish Church,

Snettisham, King's Lynn, Norfolk. The register reads:

John Holmes Junr. Esq. of the Parish [of] Marybone [Marylebone]

in the County of Middlesex, Batchelor [sic] and Ann Lindsay Daniel of

this Parish, Spinster and a Minor, were married in this Church by

Licence and with Consent of her Father ...

The spelling of the

bride's family name was variable. The groom signed the register as "John

Holmes Junr."; the bride signed as "Anne Lindsay Daniell". Her father signed as "Thomas Daniell".

RH: A listing in A Review of the Laws of the United States of North America, the British Provinces, and West India Islands, published in London in 1790, provides A List of the Principal Lawyers in the British Provinces, &c. ...

DOMINICA

John Natson, Esq. chief justice

Thomas Daniel, Esq. attorney-general

Thomas Yeo, Esq. sollicitor general [sic]

Alexander Stuart, Esq. justice of the vice-admiralty court.

Spelling remained inconsistent. The Norfolk Chronicle for March 1806 has this:

17 [March].--Died, at Snettisham Lodge, Mr. Thomas Daniell, Attorney-General of Dominica.

In 1909, the Rev. F. J. Gibbings, M.A., Vicar of Snettisham, noted that there was a marble slab in the North Transept Wall of St Mary's. The inscription read: "To the beloved and ever respected Memory of Thomas Daniel, Esq. Attorney General of the Island of Dominica, who died at Snettisham, the 17th day of March, 1806, aged 53, and is interred near this place." However he also noted the discrepancy of age in the Burial Register: "1806, March 24. Thomas Daniel Esq. aged 73 [sic] died March 17."

Footnote: I wonder if there might be some family connection to Thomas Daniel, the subject of a memorial in Bristol Cathedral: "Sacred to the Memory of / THOMAS DANIEL Esq / a respectable Merchant / of this City / who was born in Barbados / on the 14th March 1730 / and he departed this life / on the 23rd February 1802".

Thomas and John Daniel owned the Great Weston Cotton Works, Barton Hill, Bristol, and had nearly 4,000 slaves on six islands in the West Indies. That particular Thomas Daniel was one of the biggest sugar merchants, so rich

and powerful indeed that he was known as 'the King of Bristol'. Thomas Daniel and Sons of Bristol was active between 1785 and 1846 and worked closely with the Society for the Propogation of the Gospel. Coincidentally, the Bristol Thomas Daniel had a daughter called Anne - but she married Stephen Cave in 1787 and died in 1851.

The first child born to the newly-married John Holmes III and Anne Lindsay Daniel was a daughter, Anne Lindsay Holmes (1803-1884), the future wife of John Agnew.

Their second child, a daughter, Isabella Holmes (1805-1899), was born on 10 May 1805.

Sadly, all did not go well at, or just after, this second birth.

Monthly Magazine and British Register, Volume 19, Issue 1. Page 621, 1 July 1805:

Died. … At Cheltenham, … In child-bed, Mrs Holmes, wife of John H. jun.

esq. of Belfast, and daughter of Thomas Daniel, esq. attorney-general

of Dominica.

The death had been listed six weeks earlier in the Belfast News Letter for 21 May 1805: "Mrs Holmes, at Cheltenham, wife of John Holmes, jun. of Belfast".

Did John Holmes III return to Donaghadee for a short time after his wife's death?

He (or perhaps his father?) is named as being a party to the post-nuptial agreement of a Dr Wilson in Donaghadee in 1806.

On 18 May 1825, three and a half months before the death of his father, the Belfast News Letter listed the death of "Mr John Holmes jun., at Honiton in Devonshire, formerly of this town". The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for Thursday 19 May 1825 was slightly more expansive:

Tuesday died, at Honiton, Devon, in his 51st year, John Holmes, jun.

esq; of Lansdown-place, West. This gentleman possessed great literary

talents, and his death is deeply regretted by his family and friends.

What were these "great literary talents"? John Holmes, jun., Bath, is listed as a subscriber to The Maniac, a tale, or, A View of Bethlem Hospital: and The Merits of Women, a poem from the French, with Poetical Pieces on Various Subjects , original and translated. By A. Bristow [Amelia Bristow]. London, printed for J. Hatchard, 1810.

Amelia Bristow (not mentioned in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, RIA / Cambridge University Press, 2009) was a northern Irish-born novelist, poet, translator and magazine editor (the Christian Lady's Friend and Family Repository, described by Nadia Valman as "a women's conversionist periodical"). Amelia was based for a long time in London. She was said to have been born c.1783.

There are many northern Irish subscribers listed in this early work from 1810 (Amelia's Lissau trilogy dates from the 1820s), perhaps reinforcing the Bristow/Belfast connection - though, what exactly that was, is not clear.

Was she related to the Rev William Bristow (1736-1808), the Vicar of Belfast from 1772 until his death, and also Sovereign of Belfast, 1786-1788, 1790-1796 and 1798?

Martha McTier was not a fan, referring to William as "our great Pomposo". William and his wife Rose had three sons and four daughters.

William's brother was Sir James Bristow who enjoyed the company (to coin a not very original phrase!) of Mrs Thomas Bunbury Isaac (formerly of Bloomfield House).

Under

'B' in The Maniac's subscriber list are Miss Bristow, Birchill, Antrim, 8

copies; Rev. Charles Bristow, 2 copies; Mrs D. Bristow; Miss Bristow,

Belfast; and Mrs Bunbury, Moyle, Carlow, 2 copies.

Under

‘H’ are Mrs Houston, Greenville, Belfast, and Miss Harriet Hutchinson,

Castle Hill, Belfast (there must surely be a connection here with Bloomfield’s Mrs

Hutchinson (see 1776-1798) and the Garner family of Castle Hill).

Many important families in and around Belfast are represented –

including 4 copies for the Marquis of Donegall and 2 copies for the

Marchioness; and one each for Henry Joy, Esq. Belfast, Mrs [Thomas] Bunbury Isaac, Holywood House, Belfast, and Simon Bunbury Isaac, Esq. 59th Reg.

The Bath Chronicle, Thursday 28 December 1826, advertised the sale by auction of John Holmes III’s substantial house in Bath:

Capital Freehold DWELLING-HOUSE, with Garden

No.3, West Wing, LANSDOWN-CRESCENT.

To be SOLD by AUCTION, by Mr. STAFFORD,

At his Rooms in Milsom-Street, Bath,

By direction of the Executors, on Monday Jan 1st, 1827,

The Substantial and Modern-Built Dwelling-HOUSE, with Flower Garden in the rear, extending 123 feet; and containing handsomely arranged suites of apartments, of good elevation, in a dining room, 18 ft. by 15 ft. 7 in.; a back parlour, 14 ft. 10 in. by 16 ft; a wide staircase, which is lighted by a central dome lantern from the roof, leads by a mahogany hand-rail to a front drawing-room, 17 ft. 8 in. by 21 ft. 10 in., and a back ditto, 19 ft. 7 in. by 14 ft. 6 in., with statuary marble chimney-pieces, register stove grates, and modern fittings; 3 large attic bedchambers, and 4 servants’ sleeping-rooms; with a range of large closets on the landing.

There is an excellent kitchen, with every desirable requisite; a housekeeper’s room, with two large cupboards; and a butler’s pantry, amply fitted up. The basement provides a brewhouse, with a large copper, and a plenitude of water, with wine and beer cellars united. Properly placed is a water-closet, with mahogany fittings, supplied by a force pump; with other essential domestic offices.

Late the Residence and Property

Of JOHN HOLMES, Esq, deceased.

The tenure is Freehold, subject to an annual ground-rent of 10 guineas.

To be viewed by tickets; and publicly viewed two days preceding the sale; and any further particulars may be known on application to Mr. Clarke, solicitor, St. James’s-parade; or Mr. Stafford, Milsom-street.

Lansdown Crescent, Bath, drawn in 1826 by Robert Woodruffe (1805-1869). Courtesy of Victoria Gallery, Bath. See more here.

Pic below: 3 Lansdown Crescent.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland has a copy of the will of John Holmes Jun. (=John Holmes III) of Lansdown Crescent, Bath, Esq., dated 28 May 1822. He died on 17 May 1825 and the two executors were (1) his father, named as John Holmes of Donaghadee, who died in the first week of September 1825, and (2) his cousin, John Holmes Houston of Belfast.

It reveals a fascinating surprise: a whole other family. I had wondered how John Holmes III had brought up his two daughters in Bath. How often did they return to Belfast or Donaghadee? Perhaps not that often after all.

He would have employed a nanny to look after Anne Lindsay and Isabella. That may well have been 'Bridget Sophia Perry [1796-1845] of the City of Bath, a single woman'. John Holmes III states in his will that John Holmes Perry [c.1813-1883], Charles Holmes Perry [c.1816-?] and Henry Holmes Perry [c.1817-1887] were 'three of my natural children by her'.

What did his church-going father, John Holmes II, make of that?

Many Perry families can be found at that time in and around Devon and Somerset. Might Bridget's family have been from Honiton?

And was there any contact in later years between the Perry boys and their families with the two daughters who lived in Belfast?

The boys seemed to have been well provided for in their father's will; presumably there would have been ongoing contacts through the executor, John Holmes Houston.

See much more about the Perrys in the Holmes family PDF above (alongside the pic of John Holmes II).

Footnotes: Apart from John Holmes III's "great

literary talents", was he the John Holmes jun. listed as a passenger

arriving in New York on board the line ship William Thompson, 32 days from Liverpool, with dry goods, hardware, &c. [followed by a lengthy list of companies and names] (Evening Post, Friday, September 6, 1822)?

It's unlikely he was the John Holmes, junior, mentioned in the London Gazette,

21 August 1824, page 1377, stating that "Notice is hereby given, that

the Copartnership subsisting between us the undersigned, Eusebius Holmes

and John Holmes the younger, of the City of Bristol, Merchants, trading

under the firm of Eusebius and John Holmes, junior, is this day

dissolved by mutual consent: As witness our hands the 16th day of August

1824. [Signed] Eusebius Holmes. John Holmes, jun."?

Eleven months before the late John Holmes III's house in Bath was sold, page 3 of the Belfast Commercial Chronicle for Saturday, 4 February 1826, announced a marriage: 'On the 3d ult. at St. Anne’s Church, Belfast, by the Rev. A. C. Macartney, JOHN AGNEW, Esq. Sovereign of Belfast, to ANNE LINDSEY [sic], eldest daughter of the late John Holmes, Esq. and grand daughter to our late respected townsman, John Holmes, Esq. of DonegalI-place.'

At least the Belfast News Letter for 7 February 1826 managed to spell the bride's name correctly, noting the marriage of John Agnew (Belfast) and Anne Lindsay Holmes (Bath).

Not so the Enniskillen Chronicle and Erne Packet on Thursday 9 February 1826:

MARRIED,

On the 3d inst. John Agnew, Esq. Sovereign of Belfast, to Anne Lindsey [sic], eldest daughter of the late John Holmes, Esq. Lansdown Crescent, Bath, and grand daughter to the late John Holmes, Esq. of Donegall-place, Belfast.

It's interesting that the wedding was on 3 February and there exist several memorials of leases "for 3 lives renewable for ever", for the Donegall estate, dated 4 February 1826. They're a fascinating record of the business partners associated with the Marquis - and with John Agnew:

"Marquis of Donegall 1st Part and Rt. Hon.

Geo. Chichester Macartney, Earl of Belfast 2nd Part and John McCance,

Esq., and John Agnew, Esq., (Belfast) 3rd Part and Rev. Arthur

Chichester Macartney (Vicar of Belfast) and Jas. Watson, Esq.,

Brookhill, Co. Antrim 4th Part and Thos. Verner, Esq., and Andrew

Alexander, Esq., Belfast 5th Part and The Rt. Hon. Ld. Baron Dufferin of

Ballyleidy, Co. Down and Sir Stephen May, Belfast 6th Part and The Most

Hon. John Loftus, [2nd] Marquis of Ely and Chas. Henry Tottenham, Esq.,

Clonfarm, Co. Leitrim 7th Part ..."

The couple had two children. The Belfast News Letter of 28 November 1826 recorded the birth of a daughter, Anne Lindsay Agnew (1826-1881). The Belfast Commercial Chronicle of 29 November stated: "On the 19th inst, the lady of John Agnew Esq, Sovereign of Belfast, of a daughter."

As already noted, a son, John Agnew, jun. (1830-1855), was born "at Newgrove" on 15 January 1830.

Later we'll see that John Agnew had a great interest in horticultural pursuits - but family life was not a bed of roses.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), at D3113/7/34, has a letter written by Michael Ferrar (1796-1884) to the historian George Benn (1801-1882). Michael was the son of William Ferrar, Belfast's first magistrate of police.

The letter provides a tragic insight to the Agnew family:

Camden Street, 29th November 1879

Dear Mr Benn

… The late John Agnew married about January 1826, Miss Holmes, daughter of an old and eminent merchant of Belfast long retired who lived in Donegall Place. They had a son and a daughter; the latter lives with her mother in University Square. The son was an utter reprobate drunkard and blackguard shunned by all who knew him or his father.

Some dozen or it may be 15 years since [= ago], he was found dead in a hay loft in Antrim, having lain down in a drunken bout. I knew his father very well, he being an intimate of my father’s, but never heard a word about his parentage or if he was of any business or profession.

All I remember is that he was an intimate of Lord Donegall’s family and often Sovereign of the Town, being the last who held that office before the present Corporation came into office about 1841 or 42. He was a perfect gentleman in manners and a tall and handsome man, but you probably recollect him as well as I do. It is most unlikely his son was ever an intimate of the old Poor House; if he had I was almost sure to have heard of it and think Dr McKeown has jumbled up Allan Brown with Agnew, both being sons of Sovereigns and [the] former certainly lived in it several years and died in it.

I know poor Mrs Agnew had a weakness for her son’s failings and would surely have saved him from some of their consequences. I never knew the young man. His father died many years before him. I forget when. …

Woodcut from R.M. Young's

Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast, 1892.

The Belfast News Letter, 16 November 1855, recorded the son's death: "Nov 12. John, only son of the late John Agnew of Bloomfield, Co. Down".

Michael Ferrar wasn't quite correct. As will be detailed later, John Agnew, sen., was actually the last but one Sovereign - not the last.

His activities as Sovereign can be gleaned from newspapers and official documents, but there's little known about his previous business dealings or about where he came from. Ferrar described him as an "eminent merchant", but he seems to just appear on the Belfast scene, already deemed a gentleman of means, listed at the Nelson Club in Bradshaw's 1819 Directory, and as someone well-acquainted with the Donegall family.

Remember that newspaper report from November 1819 quoted near the top of this webpage?

It told of John Agnew riding with the Marquis of Donegall's harriers in the company of William Wallace Esq.* and Lord Edward Chichester (1799-1889).

* It's likely that this was William Wallace Legge (1789-1868). He was the eldest son of Hill Wallace and Elinor Legge (daughter of Alexander Legge of Malone House). William Wallace assumed the additional surname Legge in 1821 when he succeeded to the maternal estate of Malone House. He was High Sheriff of Belfast in 1823.

But there's also a slightly earlier sighting of John Agnew.

This is from page 2 of the Belfast Commercial Chronicle for Saturday 08 February 1817:

TO

Thomas Ludford Stewart, Esq.

SOVEREIGN OF BELFAST

We the undersigned Inhabitants of Belfast and its neighbourhood, holding in the utmost abhorrence the late diabolical and vile attempt made by a treasonable and tumultuous mob, on the sacred person of his Royal Highness the PRINCE REGENT, on his return from Parliament; request you will convene, on an early day, a Meeting of the Inhabitants of this Town and neighbourhood, for the purpose of expressing our utter reprobation of the treasonable proceedings manifested on that occasion, and our loyal and warm expressions of congratulation on his Royal Highness’s providential escape.

Belfast, 4th February, 1817.

A lengthy list of names follows, headed by Donegall, Belfast, and including the likes of Stephen May, Narcissus Batt, Arthur Crawford (of Bloomfield House of course), Cunningham Greg and William Tennent.

And there, in the midst, is John Agnew.

Maybe there’s an even earlier sighting of our John Agnew in another newspaper listing:

Page 1 of the Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Saturday 09 September 1809, lists ‘The following Gentlemen [who] have taken out Certificates for Killing Game for the present year, commencing 25th March last’. They include both ‘John Agnew, of Purdy’s-burn’ and ‘James Kelsey, Purdy’s-burn’.

Mr. Kelsey had been listed by the same newspaper in 1807 (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Monday 09 November) as ‘James Kelsey, Purdysburn’ where the list was described as ‘Names, Places of Abode, &c …’ This time, ‘Purdysburn’ is given as a single unhyphenated word without an apostrophe.

Purdysburn House, dating from the first decade of the 18th century, had apparently lain vacant after the Bishop of Down and Connor left it in 1798. It was eventually sold in 1811 to Narcissus Batt (1767-1840), the Belfast merchant and banker. During those vacant years, the surrounding land was let out for short terms. Was this 1809 John Agnew the young future owner of Bloomfield and was his involvement then only with the Purdysburn land? See the history of Purdy’s Burn here. If John Agnew's gravestone inscription is

correct, he was born around

1790. If true, he was already "a gentleman of means" at the age of 29;

barely into his early 30s when he was involved with the Donegall

family's finances; only 33 when first appointed Sovereign.

Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Monday 26 June 1826, page 2:

On Saturday, the 24th inst. a meeting of the Sovereign and Burgesses was held at the Assembly-Rooms, for the purpose of electing a Sovereign for the ensuing year, pursuant to Charter, when John Agnew, Esq. the present Sovereign, was again unanimously re-elected. — We congratulate our fellow-townsmen on the judicious arrangement of the Burgesses in re-appointing this Gentleman to fill the situation of Chief Magistrate — the duties of which he has executed so ably, attentively, and impartially, as to win the good opinion of all classes.

Before considering John Agnew's role as Sovereign,

it's worth looking at the wills of his daughter and widow, both called

Anne Lindsay Agnew.

John Agnew's wife long out-lived him. She even out-lived her daughter.

However it's the daughter's will which is of most interest. It reveals the close friendship with the families of both William Russell of Edenderry and John Russell of New Forge. Also with the Blakiston-Houstons of Orangefield. She makes provision for the family's servants and doesn't forget her aunt, her mother's younger sister, Isabella Holmes.

It's too early for the suffragettes, but there's a telling final comment: "All bequests made by me to females to be for their separate use and free from marital debts control or engagements."

Digression: Alex Lockhart, solicitor

There’s a nice connection between the family of Bloomfield’s previous occupant, Arthur Crawford, and the Holmes and Agnew families.

It’s through the Agnew’s solicitor, Alexander Lockhart, of Crawford and Lockhart, who signed the wills of both mother and daughter.

His parents were Alexander Lockhart (c.1788-1848), a gardener, and Françoise Marie Richenet (1797-1862) from Vevey, Switzerland. They were married in Armagh, possibly in St Patrick’s CoI Cathedral, on 06.05.1826 by Cosby Stopford Mangan, rector of Derrynoose. Alexander sen. was described in the Belfast News Letter as “Gardener to His Grace the Lord Primate [Lord John George Beresford]”.

Their son, Alexander, the solicitor in

question, was born in Marylebone, London in 1829. He served as a law

clerk to Henry Russell of the law firm Crawford & Russell (Crawford

being Arthur’s son, William Crawford, brother-in-law of Earl Cairns of

Garmoyle). Henry was the son of John Russell and his wife Catherine

Helen Holmes (John Agnew's sister-in-law).

LH Pic: The bell-push for Crawford, Lockhart & Turnbull, Linenhall Street, Belfast, March 2013.

Crawford and Lockhart's clients included the cream of society, not least George Dunbar, of Woburn House, whose wife was Harriet Beresford, niece of Lord John George de la Poer Beresford (1773-1862), the Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland. It was Harriet and her sisters to whom Françoise Marie Richenet had come as governess or French teacher; Marie remained a friend of Harriet's for 40 years.

Coincidentally, Alexander married a Margaret Agnew - no connection with our John Agnew as far as is known!

It seems likely that when Russell died in 1869, the firm became Crawford & Lockhart, surviving as such to this very day in Belfast. Lockhart died in 1892 at his home, Scoutbush, Trooper’s Lane, Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim.

He was succeeded in the business by his son Alexander Agnew Lockhart who was also a signatory to the Agnew wills.

More information on this Lockhart family, courtesy of Elayne Lockhart, is available online here. The sad story of John, one of Alexander’s brothers, is accessible here.

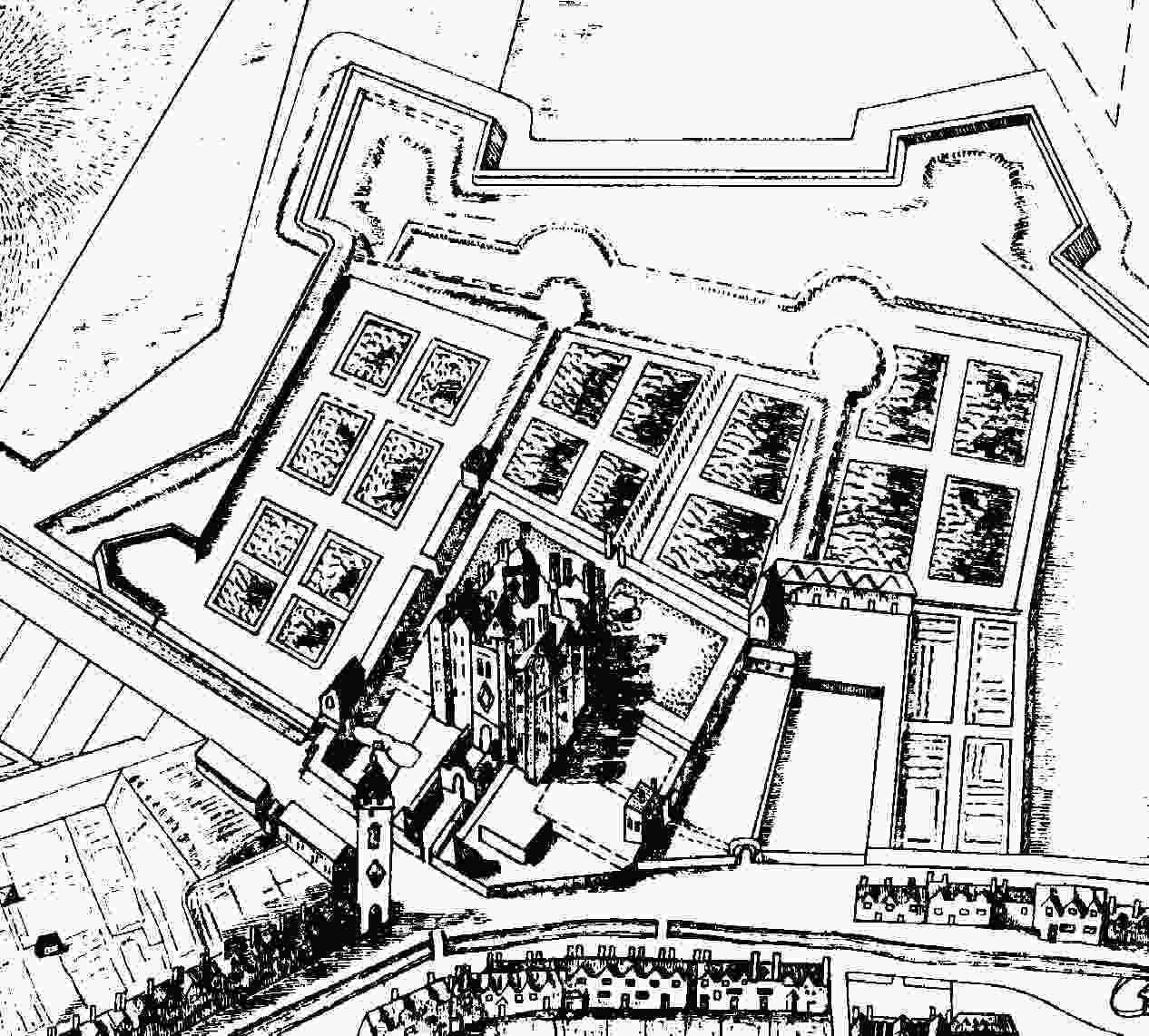

In 1612, King James granted to Sir Arthur Chichester the town, castle and surrounding areas of Belfast.

The following year, 1613, the town was incorporated by a Charter which established that "from henceforth [it] shall be for ever one whole and free borough of itself by the name of the borough of Belfast …"

The Corporation was entitled "The Sovereign, Free Burgesses, and Commonalty of the Borough of Belfast".

Its constituent parts were:

One Sovereign

One Lord of the Castle

One Constable of the Castle

Twelve other Free Burgesses, and

Freemen, without limit to the number.

RH pic: Belfast Castle and gardens as shown in Thomas Phillips' map, 1685.

The Corporation suggests a sense of organisation and perhaps even democracy when listed like that.

In practice,

for well over 200 years, tight control of Belfast was exercised by the

Chichester family (the Earls of Donegall from 1647, and the Marquises of

Donegall from 1791). The Corporation consisted solely of Chichester /

Donegall nominees. That control only ended after the passing of the

Municipal

Corporations (Ireland) Act in 1840 and the subsequent reshaping of the

Corporation.

From Robert M. Young's The Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast, 1613-1816, Belfast, 1892.

The list of Belfast Sovereigns in the early 19th century makes interesting reading, particularly in the light of an ever-increasing number of vociferous reformists. They were dissatisfied with the Corporation, and sought Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform.

In July 1813 there were also serious riots caused by friction between marching Orangemen and those opposed to them. Two men were shot dead.

A town meeting was called, adjourned and rescheduled with the Sovereign, Thomas Verner, in the chair. The former Sovereign, Rev. Edward May, called for a further adjournment. It was during the resulting fracas, that an influential merchant, Dr. Robert Tennent, put his hand on May's arm, as he was wont to do when addressing people. The Belfast Monthly Magazine (BMM) described May's over-reaction:

“Mr May violently rushed forward and seized him by the throat, ordering

some person near him, seemingly brought there for the purpose, to drag him to the Black Hole; which, to the astonishment of all present, was literally

complied with.” The italics are from the BMM.

Tennant was charged with striking May, found guilty, given three months' imprisonment and fined £50.

The BMM, October 1813, didn't agree. Tennent's conduct was described as "unimpeachable". He "was prosecuted on political grounds,

and he was punished, not for his own supposed political sins only, but

to deter others from following his example" (the italics are again from the

BMM).

At the same time, Tennent was inadvertently drawn into another court case in which a travelling pedlar, Jane Barnes, accused the Sovereign,

Thomas Verner, of rape.

Verner was acquitted. The BMM clearly thought differently. "Jane Barnes was threatened with a prosection for perjury, but we have heard of no effectual means to carry these threats into execution. Mystery, or to use the newly adopted diplomatic phrase, mystification hangs over the business. But there is a plot somewhere!" (the BMM's italics again).

Some knowledge of the immediate Donegall family background is essential in all of this.

The First Marquis (1739-1799) was, by any definition, an absent landlord. He was born and lived in England.

The future Second Marquis (1769-1844), then Lord Belfast, was in and out of debtors’ prison in London from 1794 because of his huge gambling debts.

His release was procured by Edward May,

"a moneylender and shady

attorney". He paid off Lord Belfast’s gambling debts – seemingly on condition that Lord Belfast married his daughter Anna (1795). May succeeded to the title of Second Baronet of Mayfield, Waterford, on the death of his father in 1811.

Lord Belfast was apparently unaware that Anna was May’s illegitimate daughter (May’s other three children were also illegitimate) and under age. On the death of his father in 1799, Lord Belfast became the Second Marquis of Donegall. When the pressures of his many creditors got too much, he returned to live in Belfast in 1802, bringing with him the May family.

Thus it was that the May family inveigled its way into Belfast society, power and politics, and the church.

Problems came to a head in 1819 when the Second Marquis’s son and heir, the Earl of Belfast, was about to marry the Earl of Shaftesbury’s daughter. Shaftesbury received an anonymous letter informing him that the Marquis's marriage in 1795 had been, to say the least, irregular. It had been carried out under special licence and not by the calling of the banns.

According to the 1753 act, this would then also have rendered his daughter’s children illegitimate and, perhaps worse at that time, meant there would be no inheritance from the Donegall family.

The marriage was called off.

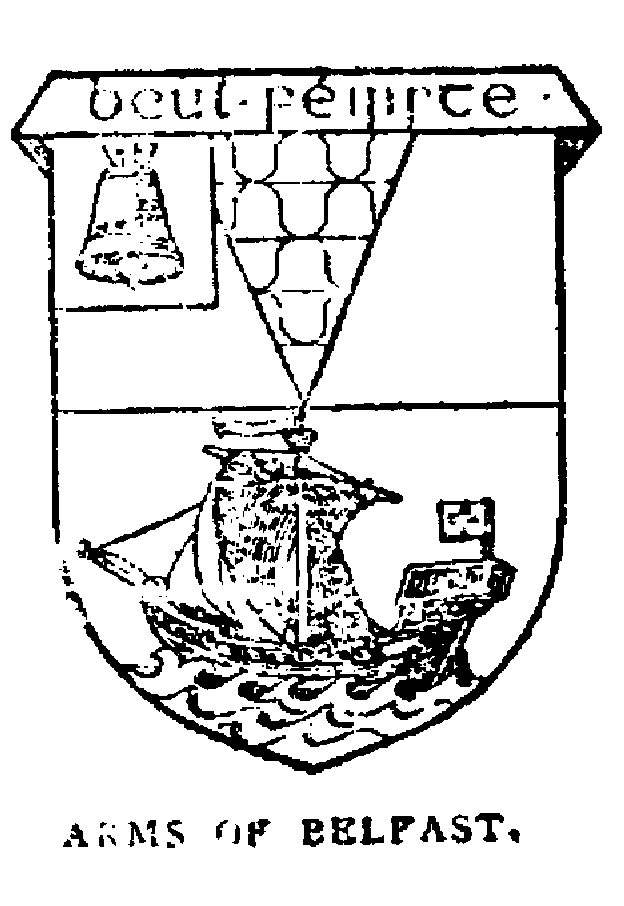

RH pic: The original seal of Belfast Corporation from the cover of Robert M. Young's The Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast, 1613-1816, Belfast, 1892.

It was a big news story - a national one. Technically, all seven children of the Marquis's marriage to Anna May were deemed illegitimate.

The situation was only resolved in 1822 when the House of Commons passed an amendment to a 1753 act which had originally been aimed at reducing the number of clandestine marriages. The amendment legitimised the Donegall/May marriage in retrospect and all was well once again - apart from the Marquis's finances.

These too were resolved to some extent (i.e. in the short term) towards the end of 1822 when the Marquis began raising money to clear his debts by selling 'perpetual leases'. Hence the rash of legal documents over the next decade in which "John McCance, Esq., and John Agnew, Esq., Belfast" were named as being "of the second (or third or whatever) part".

As already mooted, the list of Sovereigns was completely dominated by the Chichester family.

In 1835, the Appendix to the first report of the commissioners appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations in Ireland stated that only six freemen were then known to exist. In A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, published in 1837, Samuel Lewis noted a decline: "The freedom of the borough is acquired only by gift of the Sovereign and free burgesses; at present there are no freemen."

The commissioners commented that "the same person is constantly re-elected [as a burgess], or holds over, for a long series of years, until the 'patron,' the Marquis of Donegall, expresses his desire that another person should succeed to the office. The Lord of the Castle is a member of the Corporation by tenure of the castle of Belfast. The Marquis of Donegall holds that office, and it appears to have been in his (the Chichester) family from the date of the Charter."

The commissioners outlined the many roles of the Sovereign, including being the returning officer for elections, the chief magistrate, the treasurer of the Corporation, clerk of the market, and a commissioner of police. He also held a Sovereign's Court twice a week and he received the tolls of £500 per year from Smithfield market, etc. They finished, perhaps on a positive note, pointing out that he did not have a mansion house.

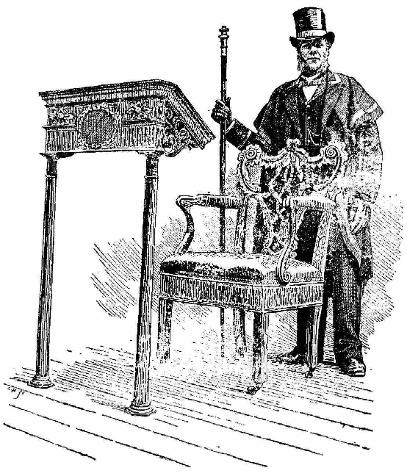

LH pic: The Sovereign's seat and desk from Robert M. Young's The Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast, 1613-1816, Belfast, 1892.

Details of the Sovereign's many roles from that 1835 Appendix are given in this PDF:

The final paragraphs of the commissioners’ report are damning:

The Constitution we have described, probably was intended to vest some of the most important, and has, certainly, long operated, virtually to vest the whole of the corporate powers in the Lord of the Castle of Belfast, who has been esteemed "the patron." The free burgesses having usurped the power of excluding the inhabitants, thereby became the governing body. They had the power of self-election, and have all become, in effect, the mere nominees of the Lord of the Castle.

No Roman Catholics have been admitted since the relaxation, in the year 1793, of the penal laws previously affecting them.

The Corporation, as now conducted, embraces no principle of representation, and confers on the inhabitants no benefit. No power of control or check is preserved; the proceedings are carried on without publicity, and the consequences have been, that great neglect and abuse of trusts reposed in the body have occurred, and have remained so long concealed, that the utmost difficulties now lie in the way of any attempt to correct them.

… as the town increased [in size], we find the Legislature apparently treating the Corporation as a body unsuited, from its constitution, to discharge, with efficiency and satisfaction, the important trusts which had been confided to its care; and that, accordingly, local statutes have been enacted at different periods, by which the management and control over municipal interests have in a great measure been withdrawn from the Corporation, and vested in local boards, the majority of whose members are elected by the inhabitants, under the various regulations of those statutes.

Under these circumstances, we found that the Corporation had ceased to be an object of interest to the inhabitants. Its natural functions had been superseded by the establishment of the local boards, and its monopoly of the elective franchise by the Reform Act.

The irresponsible nature of its constitution, united with the secrecy of its proceedings, would appear to render it peculiarly unsuited to the management and control over public affairs. The abuses which may result from the existence of a public body so constructed, are clearly exemplified in the dissipation of the charitable funds intrusted to the management and distribution of the Corporation of this borough.

Sovereigns of Belfast, 1802-1842

Arthur Chichester in 1802

Not sure who this is! Hardly the Marquis's nephew. Arthur (1797-1837) was the eldest son of Lord Spencer Chichester, second son of the first Marquis. He was created Baron Templemore in 1831. Rather too young to be Sovereign in 1802.

James Edward May in 1803-1806, 1809, 1810

He was the father of Anna, the Marquis's wife, and he acted as the Marquis’s marriage broker. His reward as the Marquis's father-in-law was being MP for Belfast 1798-1800 and 1801-1814.

In 1811 he succeeded to the

Baronetcy of Mayfield, Waterford, on the death of his father, the First

Baronet of Mayfield.

Rev. Edward May in 1807, 1808, 1811, 1816

He was Anna’s brother and Vicar of Belfast.

Thomas Verner in 1812-1815, 1819-1822

He was married to Elizabeth, the sister of Anna May. He was the brother-in-law of Rev. Edward May and an Orangeman.

Thomas Ludford Stewart in 1817, 1818

He was an attorney, the Marquis's legal agent, and he leased a house in the grounds of the burnt-down castle in Castle Street.

John Agnew in 1823 (part),1824 (part), 1825,1826 and 1834-1840

Agnew was "an intimate of Lord Donegall". During this period, he was the one who served for the longest time as Sovereign. More information below, though much remains to be discovered.

Andrew Alexander in 1823 (part) and 1824 (part)

More information about Alexander is given below. Like Agnew he was one of the parties to many of the leases which Donegall renegotiated or 'sold' in perpetuity for an ongoing rent and a lump sum 'fine', thus providing his Lordship with instant cash.

Rev. Lord Edward Chichester in 1827

According to Sir Stephen May, Chichester was elected, but did not serve.

Sir Stephen Edward May in 1828-1833

He was the Marquis’s brother-in-law, brother of Anna, Elizabeth (married

to Thomas Verner) and the Rev. Edward. His father was Sir James Edward

May. He was the MP for Belfast 1814-1816 and he succeeded his father in

1814, becoming the Third Baronet of Mayfield.

Thomas Verner, jun., in 1841, 1842

He was the son of Thomas Verner and Elizabeth May.

This is how Michael Ferrar of Camden Street, Belfast, described some of those family connections to the historian George Benn in a letter dated 15 November 1878.

... the late Sir [James] Edward May, Bart., which title is extinct, when Mr May was M.P. for Belfast, nominated by Lord Donegall. He had two sons and two daughters, the eldest of [the] latter married the 2nd Marquis of Donegall, and was mother of the present peer - the second married Mr Verner (Tom) often Sovereign of the town, grand uncle of [the] present baronet.

The elder brother, Stephen, was one of the many thousand English travellers who were in France when the war was renewed in 1803, and who were detained by Bonaparte, 11 years until his deposition in 1815, in revenge, I was told, for the English seizing every French merchant vessel in English harbours.

After his return, he became Collector of Customs here, succeeding the Honble Mr Skeffington on his becoming Lord Massareene. His sister the Marchioness got him knighted by the Lord Lieutenant, as he could not succeed to his father's baronetcy, all whose children were illegitimate ...

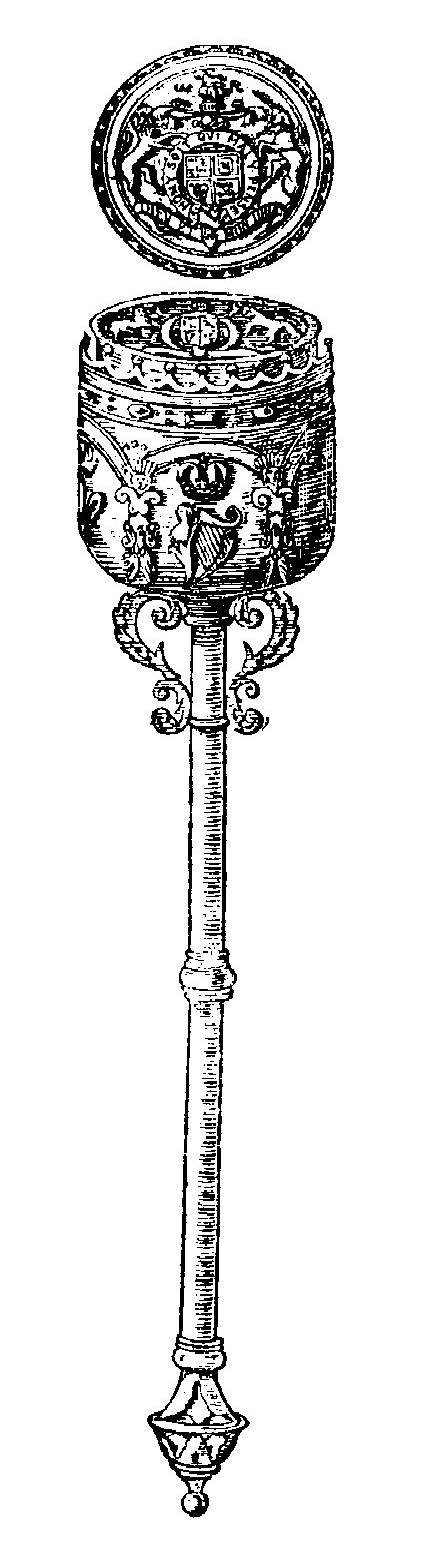

RH pic: The large Corporation mace - an illustration from Robert M. Young's The Town Book of the Corporation of Belfast, 1613-1816, Belfast, 1892.

John Agnew was first appointed Sovereign of Belfast in 1823, but for some reason, he resigned and was replaced by Andrew Alexander.

In 1815, Andrew Alexander (1781-1824) of Belfast, Alexander Cranston of New York, John Woodward of Lexington, Kentucky and John Peter Schatzell (1776-1854), also of Kentucky, formed a partnership “for the purpose of transacting mercantile business in Kentucky”. When Schatzell dissolved the partnership in 1817, the subsequent legal wrangles lasted for many years. One source (the Texas State Historical Association online re Schatzell) states that “At the center of the dispute was a twenty-two-year-old female servant named Chloe, property of the partnership.”

The Alexander and Cranston families, related through marriage (Cranston was married to an Alexander) and business, bought a grave in Clifton Street graveyard – “The burying ground of the Alexander and Cranston families”. A neighbouring headstone records the burials of John Alexander (1735-1821) of Ardmoulin, and his son Andrew, Sovereign of Belfast, who died at Ardmoulin, Belfast, on 24 October 1824, aged 43 years. (Source: see Belfast Clifton Street Cemetery records, also online)

In 1824 Andrew Alexander was re-appointed, but when he died just a few weeks later, John Agnew was appointed in his place.

John Agnew remained as Sovereign for the next two years, 1825 and 1826.

He was again appointed in 1834 and continued to serve through to 1840.

Thomas

Verner, jun. was Sovereign for the last two years of the old order,

1841 and 1842, while John Agnew remained as one of the Town's 12 Burgesses.

On the right is the summary of the Sovereign's role from Thomas Bradshaw's Belfast General and Commercial Directory for 1819:

The Sovereign has the government of the markets, the regulations of the cranes and weights, and all things respecting the sale of provisions, &c. brought into the town, of which he is the chief magistrate, and for the time being also a magistrate of the county of Antrim, ex-officio. By patent, he is clerk of the market, which gives him the power, by himself or by deputy, of settling all matters relative to it; certain established duties and customs being payable to him, out of the sale of different articles exposed in the market, from the revenue of which he is paid, and the other expenses of the situation defrayed.

Not much changes over the years in the north of Ireland.

John Agnew was caught up in the riots of July 1835 which followed an order from the Lord Lieutenant in Dublin that there should be no processions and no arches. Red rag time! What price a Parades Commission?!

The Select Committee of the House of Commons sought the truth of the affair after this report:

No processions; serious rioting on the evening of the 12th, in consequence of three arches being erected (two orange and one green); it was considered necessary for the military to be brought; the sovereign and two magistrates present to assist the police in restoring order; the military was attacked while an Orange arch was removing; A.M. Skinner, esq. [sic] present, when it was considered necessary to fire; a woman, named More [sic], a Protestant, was killed, and several wounded; the green and one orange arch removed; one orange left remaining; serious rioting in the same place (Sandy-row) on the morning of the 13th.

When the police magistrate, C.M. Skinner, esq. J.P., ordered the removal of the arches, trouble flared.

John Agnew and his colleagues apparently tried to negotiate a peaceful resolution, but Skinner read the Riot Act.

He gave the orders to fire. Anne Moore was killed and William Trainer later died from his injuries.

Was the death of Anne Moore a "lawful killing"?

John Agnew attemped to steer a middle course. "Perhaps it may be proper to inform the Committee that it has not appeared in evidence that any Orangeman or Ribandman was engaged in the riot which took place in Sandy-row on the 12th and 13th July, or in any riots which have since taken place here."

Following the inquests on Anne Moore and William Trainer, "I have reason to believe from all I have heard here that both the Green and Orange arches were erected by individuals neither connected with the Orange nor the Riband societies."

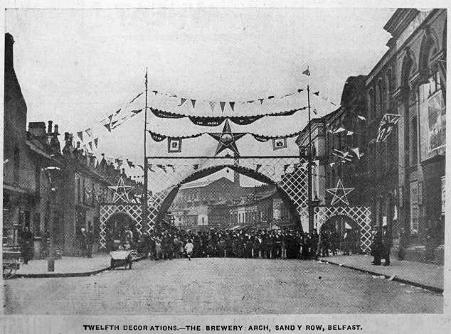

LH pic: The Brewery Arch, Sandy Row, 1932.

Pic courtesy "Ulster Canadian" on the Belfast Forum website here. Enlarge the following series of thumbnails to read from the Third Report from the Select Committee appointed to inquire into the Nature, Character, Extent and Tendency of Orange Lodges, Associations, or Societies in Ireland ...

The section is entitled:

PAPERS relating to the RIOTS at BELFAST on the 20/5th July last, and the Verdict on the body of Anne Moore.

Victoria's Coronation and a Beersbridge Mill fire

Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Saturday 08 July 1837, page 3

To be Sold or Let,

THAT HOUSE and CONCERN in DONEGALL-PLACE and FOUNTAIN-STREET lately occupied by HUGH MONTGOMERY, Esq.

and now by JOHN AGNEW, Esq. and Mr. WALLACE. Apply at No.24, FOUNTAIN-STREET. Belfast, 24th March, 1837.

So what was the 'concern' or business being undertaken by Agnew and Wallace? Answers please!

Over the following few years, 24 Fountain-street was the Belfast address given on the Prospectus of the Belfast & County Down Railway. The company's solicitors were Hugh Wallace and Co., Belfast and Downpatrick.

Was this the same 'Wallace' associated with John Agnew in that 1837 advertisement?

A few years after the 1835 rioting fuss, John Agnew was in trouble once more over Belfast's lack of celebrations for Queen Victoria's coronation.

Belfast News Letter, 26 June 1838

PROCLAMATION.

It having been publicly suggested that a General Illumination on the night of the 28th Instant would be a suitable mode of celebrating her Majesty’s Coronation; the Magistrates are unanimously of opinion, after the fullest consideration, that serious inconvenience might result from such a proceeding. They, therefore, hereby prohibit it, and beg leave to recommend that the sum which would be expended on such an occasion by each householder, should be paid over to the public charities.

JOHN AGNEW, Sovereign of Belfast,

and Chairman of the Board of Magistrates.

That's what happens nowadays with those who don't send Christmas cards.

Give your money to a charity instead. But in 1838 not everyone approved.

Over 80 years later, such apathy was still well-remembered. John Agnew got the blame.

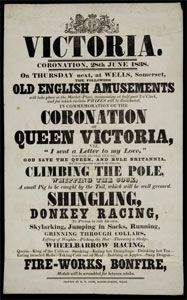

Unlike Belfast, the English town of Wells decided to celebrate the Coronation of Queen Victoria with a real community fun-day!

This is from D.J. Owen's History of Belfast, published in 1921: